Read the full text

The secret life of bonds

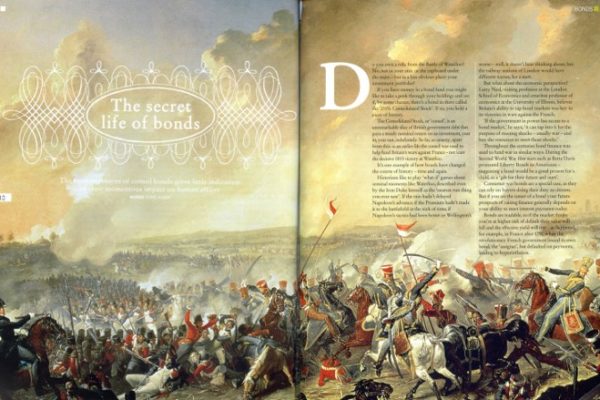

The bonds in your portfolio may have had a momentous impact on history. By Chris Alden.

Do you own a relic from the Battle of Waterloo? No, not in your attic or the cupboard under the stairs – but in a less obvious place: your investment portfolio?

If you have money in a bond fund, you might like to take a peek through your holdings – and see if, by some chance, there’s a bond in there called the “2½% Consolidated Stock”. If so, you hold a piece of history.

The Consolidated Stock, or “consol”, is an unremarkable slice of British government debt that pays a steady nominal return on an investment, year in, year out, indefinitely. So far, so unsexy, apart from this: in an earlier life, the “consol” was used to help fund Britain’s wars against France – not least the decisive 1815 victory at Waterloo.

It’s one example of how bonds have changed the course of history – time and again.

Historians like to play “what-if” games about seminal moments like Waterloo, described even by the Iron Duke himself as the “nearest-run thing you ever saw”. If the rain hadn’t delayed Napoleon’s advance; if the Prussians hadn’t made it to the battlefield in the nick of time; if Napoleon’s tactics had been better or Wellington’s worse – well, it doesn’t bear thinking about, but the railway stations of London would have different names, for a start.

But what about the economic perspective? Larry Neal, visiting professor at the London School of Economics and emeritus professor of economics at the University of Illinois, believes Britain’s ability to tap bond markets was key to victory in wars against the French.

“If the government in power has access to a bond market,” he says, “[it] can tap into it for the purpose of meeting shocks – usually war – and buy the resources to meet those shocks.”

Throughout the centuries, bond finance was used to fund war in similar ways. During World War II, film stars such as Bette Davis promoted Liberty Bonds to Americans – suggesting a bond would be a good present for a child, as a “gift for their future and ours”.

Consumer war bonds are a special case, as they can rely on buyers doing their duty as citizens. But if you are the issuer of a bond, your future ability to raise finance generally depends on your ability to meet interest payments today.

Bonds are tradable, so if the market thinks you’re at higher risk of default, their value will fall and the effective yield will rise – as happened, for example, in France after 1790, when the Revolutionary French government issued its own bond, the “assignat” – but defaulted on payments, leading to hyperinflation.

Yet even at their lowest ebb in 1797, 3% British consols were yielding not much more than 6% – a figure nevertheless unusual enough, Neal says, to motivate the then prime minister, Pitt the Younger, to impose the 1799 income tax which had the “desired effect”, he says, of “restoring the credibility of bond finance”.

Crucially, says Neal, instead of taxing irregularly to pay for war, Britain would tax to meet interest obligations – an effect known as “tax smoothing”. This meant British tax rates were less volatile than the French, and the British economy could better withstand the pressures of war.

But consols were by no means the first government bonds. Through history, governments have used many innovative ways to part investors from their cash – often to fund war.

“War is the engine of time,” says Professor Luciano Pezzolo, of the Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia, an expert in the debts of warring Italian city-states. Venice and Genoa, he says, set the ball rolling in the early 13th century with “forced loans” to its citizens, the first of a bewildering variety of long-term debt issues in the region through the next few centuries.

One innovative bond in Florence, Pezzolo says, was the Monte delle doti of 1425 – a tradable “dowry fund” which would only pay out when the daughter of the investor got married. “The main concern of parents in ancien regime Europe was to provide their daughters with appropriate dowries,” Pezzolo says. “So the government linked this concern with its financial needs.”

The scheme was attractive for a while – but decades later the city defaulted on the debt, no doubt leading to many a disappointed Florentine bride.

The first attempt at an English national debt issue, made in 1693 after defeat at Beachy Head, failed even more quickly: it was a tontine, a strange financial device in which a pool of subscribers invest in a fund.

“The total that is paid out is fixed, but as people die off, the return for the survivors keeps rising,” explains Neal, “until you get to a minimum number, which is seven. At which point, you only get one-seventh, because they want to minimise the incentive to kill off the others.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was undersubscribed.

As long as there have been bond markets, of course, there has been speculation. Before Waterloo, consols were being traded as if they were bets on the outcome of the battle.

“A number of scams are attempted,” says Neal. “In one of them, one of the stockjobbers in the London Stock Exchange [arranged] for somebody dressed up in military uniform to dash from Dover, claiming that the British had won. They hadn’t, actually” – yet – “but it created a big jump-up in prices of consols.”

At this point, of course, the scammers would sell – before the fraud was discovered and values fell. In the event, says Neal, the economist Ricardo led efforts to expel the culprits – and reimburse the victims.

Nearly two hundred years later, of course, we’re in the aftermath of a global credit crisis that has seen the collapse of one of the biggest names in banking, Lehman, and a financial crisis in Iceland that saw the country in danger of national bankruptcy.

After the banking crisis, it’s not just bond yields that markets track, but a more complex financial product: the “credit default swap” or CDS, a contract which pays out if its underlying bond defaults – with, in recent months, CDS spreads for Greece and Ireland watched more closely than most.

What’s at stake for some, of course, isn’t so much the debts themselves as the future of European integration; showing, two centuries after Napoleon, that European history is as dependent on the bond market as it ever was.

Article published in 2011